This follow-up to the initial post about µWeb’s development history is running on the long side, so I’ve split it up into two parts. This one will deal with the high-level view and an in-depth analysis of the template system. The next part will deal with the presenter, database interaction layer and the standalone server.

µWeb is tagged as a minimal-size micro web-framework, and it does deliver on that promise. The code is spread out over a core of a dozen files and some included libraries and weighs in at a bit under 5000 lines of code (see Appendix A). While small, it’s certainly not the smallest out there. The smallest (in popular use) I’ve seen so far is Bottle. It provides a full web-framework in a single file, clocking in at just over 2300 lines of code. While less code is preferred, it’s not a compelling reason to pick one framework over another. Features and the ease with which you can get things done are.

We started development of µWeb without a clear set of design goals, and a number of decisions were made with a lack of information, experience and clairvoyance (though the latter is a common problem). This means that the current product suffers a number of unfortunate flaws. A good few of these can be easily fixed and improved upon, but others would require rewriting major portions of the code base. While a rewrite is an option, it would take a serious effort and there are other, more complete and functional web frameworks readily available for use. For my own day to day work I’ve migrated to Pyramid, which provides a simple and easy interface which contains solutions for all of the most common requirements, and is easy to extend.

While many of the popular frameworks all have their own way of doing things, significant portions of them overlap. Whether this is because of the cross-pollination of good ideas, inspiration and collaboration, or simply because it’s the best and obvious way to do it isn’t relevant here. A family of broadly similar frameworks make life easier for developers as they inevitably end up working on someone else’s project, which is based off of their favorite framework. In this post, we’ll compare parts of µWeb with other frameworks (like the aforementioned Pyramid and Bottle), to illustrate the difference and how it is significant.

General shortcomings

As much as possible, I’ve grouped the flaws and problems of the µWeb framework into a small number of sections. These align roughly with the model/view/presenter pattern that µWeb follows, including one for the debugging server:

- The template system;

- The presentation layer;

- The database interaction layer;

- The standalone / debugging server.

In addition to these sections, there are a number of flaws in the foundation of µWeb itself. They don’t fit any of these sections very well, so they go in this fifth section, general.

µWeb is not WSGI-compliant

This has already been mentioned in the previous post, but it remains a significant point. There are tons of high-quality WSGI servers available, but there is only one implementation of mod_python. If you want to deploy a µWeb application, your platform must include Apache, either directly facing the web, or behind a reverse proxy. Neither is necessarily bad, but there is a definite lack of choice. It also limits your options for cloud-hosting (for example on Heroku), where WSGI application servers are the norm. Even in the beginning of 2009, when we made our choice of target platform, the trend was clear: mod_python was on its way out, wsgi was the way forward.

µWeb does come included with its own standalone web server, which at some level runs the same code as mod_python would, but this is not without its own problems and limitations.

Configuration and code are too tightly coupled

For each µWeb project, a single configuration file is assumed. The name for this file is provided in the main project file. This means that the location of the configuration file is static for the project, which may be difficult for deployments where code and configuration want to be in separate places. The same directory layout must be maintained locally and in production.

In addition, a number of configuration settings (template directory, static directory) are implied in code and need to be overridden on the class PageMaker. When altering the static content or template directory, the developer could choose to load them from the configuration, but these settings should always be read from there. This provides for both explicitness and consistency.

Paste turns the configuration vs code problem around: A web application is loaded, configured and started from a provided configuration file. This means that the application must be a Python package, but that’s a small burden given the ease of virtualenvs. Bottle has an approach similar to µWeb, but it’s a lot easier to provide it with a five line loader script which imports the Bottle app, configures it, starts it and then returns the WSGI app. The file layout requirements of µWeb make this approach more difficult.

There is no way to attach middleware

There is no convenient way of adding functionality to µWeb applications like one would add WSGI middleware to an application. There is no easily-accessible or documented way to add anything to the application before it starts, so the best that can be done is modifying the application while requests are processed.

There is a semi-persistent storage system available on the PageMaker, but installing middleware into this store has its own problems. Because a new PageMaker is instantiated for each request, there is no knowledge of whether the middleware has been installed prior. Installation and configuration of the middleware will have to be performed (or skipped) before every request. This can add significant load time to the request, but also means that middleware cannot act on whatever happened prior to that point in the code. Middleware that deals with exceptions (like Werkzeug’s excellent debugger middleware) is particularly affected by this.

In addition, because mod_python is embedded in Apache (compared to running a WSGI daemon separate to Apache), its process life is governed by the MaxRequestsPerChild directive. If this is set to a non-zero value, there will be restarts of the µWeb application, which will require re-installation of the middleware, and causes other unpleasant performance characteristics.

µWeb templates

µWeb’s template language contains the basics required of a useful template language. However, there are a number of missing features, inconsistencies and flawed behaviors that make it cumbersome to use for complex applications.

Bad handling of undefined variables

Rendering a template where an expected template variable is not included causes the output to contain the tag definition itself. [1] No error or warning is generated for the following code, making it easy for the typing error to go unnoticed, especially in more complex templates:

>>> from uweb.templateparser import Template

>>> print Template('Hello [name]').Parse(naem='Bob')

'Hello [name]'

This is related to the inability to suppress template syntax parsing. Without the ability to mark certain uses of tag syntax as body text (i.e. references and footnotes using block quotes), raising errors indiscriminately would make content creation very difficult, forcing the use of HTML entity references.

In for-loops and conditional statements, referencing an undefined variable does trigger an immediate TemplateNameError. If these need to work on potentially undefined variables, their presence can be checked using the (undocumented) {{ ifpresent [foo] }} notation.

Comparing µWeb templates to Mako, the latter is a lot better equipped to deal with missing variables: variables not present in the current context are automatically assigned an undefined type. [2] Undefined variables can be detected by comparing them to the UNDEFINED singleton. The following behaviors apply:

- undefined variables are boolean False;

- rendering an undefined variables triggers a NameError;

- iterating over an undefined variable triggers a TypeError.

By default Jinja2 is very tolerant of undefined variables: they render as an empty string, come up boolean False and iterating over them causes zero iterations. The developer can choose for strict handling of variables though, which triggers errors on access of undefined variables. [3]

Attribute and item lookup

Accessing a dictionary, list or other object that has data tucked away in its attributes is all done with a single syntax. A colon is used to indicate the access to an item/attribute: [foo:bar] will retrieve either the item or attribute ‘bar’ from ‘foo’. The following steps are taken:

- check if there is an item

'bar'in foo; - if there is not, check if there is an attribute called bar on foo;

- if there is not, raise TemplateKeyError (for printing, this causes the tag definition to be returned).

Aside from the syntax that’s very unlike Python (the dot would have been a better operator for this), the retrieval mechanism causes problems if ‘bar’ exists as an item while the attribute is desired. The solution within the current system is to define a tag function that returns a closure to return the provided attribute:

from uweb import templateparser as tmp

class Echo(object):

def __getattr__(self, attr):

return 'attr_%s' % attr

def __getitem__(self, key):

return 'item_%s' % key

def get_attr(name):

return lambda obj: getattr(obj, name)

tmp.TAG_FUNCTIONS['attr'] = get_attr

print tmp.Template('[foo:bar]').Parse(foo=Echo())

# 'item_bar'

print tmp.Template('[foo|attr("bar")]').Parse(foo=Echo())

# 'attr_bar'

For something as common as retrieving an attribute instead of an item, this is terribly clunky. Jinja2 solves this by providing two ways of accessing items and attributes. Both will resort to checking both item lookup and attribute lookup, but this way the developer has control over the order. Both of these syntaxes are identical to the Python way to access these: the dot operator and the subscript syntax. [4]

Mako has a more direct approach, where code in its output tag syntax is interpreted as Python code. While this can lead to terrible templates if abused, the approach allows for very easily understood templates because aside from tag brackets, the syntax is identical to Python. Item and attribute access look like this: ${foo['bar']} and ${foo.bar}.

Conditionals and loop syntax

On the topic of syntax, the way conditionals (if-statements) and for-loops are defined is less than ideal. The syntax for these statements is very close to actual Python, but requires the use of tag brackets around the template variables. This causes ugly markup like {{ if [some_var] }} to check whether some_var is boolean True.

It also means that {{ if [foo]['bar'] }} is valid syntax, roughly equivalent to {{ if [foo:bar] }}. The latter will also check for attributes bar as mentioned in the previous section. The implementation is to separate tags and surrounding statement text, replace the tags definitions with local variables and then eval the complete statement.

Typically, eval is a dangerous shortcut to a solution. While it’s still a shortcut, template sources are generally trusted, so this shouldn’t pose an actual problem. Thus the requirement for tag syntax for variables doesn’t change anything, other than creating a mixed syntax to write conditional statements. The tag syntax should be dropped and template variables should be included in the local scope of the eval in which the conditional is performed. This means that Python protected names can no longer be used as variable names, but this is a small price to pay for sanity.

While this section mainly discusses conditional statements, the same template-tag syntax is required in for loops. These should also have been created without this requirement, allowing direct Python usage on the in part of the statement. See Appendix C for a syntax comparison of template loops.

Inability to extend templates

The template syntax allows for most common operations: conditional execution, looping over iterables and including other templates. What it cannot do is extend an already existing template. In most template languages, you would define a base template for your application. This contains the common portions like the HTML head, your site’s header and footer, and some hooks to alter and extend these. With µWeb’s template language, this is solved one of two ways:

- The base template contains a tag expression to render a ‘body’, which is the result of a rendered template

- The page template has tag expressions to insert a header, footer and other common parts, which have been pre-rendered.

This lack of extensibility means that whole page templates are generally scattered across several different files. Returning a single web request then takes a number of render calls that need to be linked together.

Limited expressiveness in tags

Template tags have very limited expressive capability. You can retrieve attributes or items, apply one of more registered template functions to them, but that’s it. Adding to or subtracting from a template variable is a surprisingly convoluted process:

>>> import uweb.templateparser as tmp

>>> def subtract(amount):

... return lambda num: num - amount

>>> tmp.TAG_FUNCTIONS['sub'] = subtract

>>> print tmp.Template('[x|sub(1)]').Parse(x=8)

'7'

When comparing the above to the syntax required to achieve the same in either Mako (${x - 1}) or Jinja2 ({{ x - 1 }}), it becomes obvious that some things should definitely be easier.

Another thing that will inevitably come up in templates is the need to simply print the larger or smaller of two numbers, or executing any function with two or more template variables as argument. For this example, we’ll choose to print the larger of two numbers. First up is Mako. With full Python evaluation in its output tags, this is as straightforward as it gets:

>>> from mako.template import Template

>>> Template('${max(foo, bar)}').render(foo=2, bar=10)

'10'

Next up is Jinja2, which will allow you to execute functions as long as you provide them as local variables in your template. It’s your choice whether max is a local variable or the function to return the largest of n values:

>>> from jinja2 import Template

>>> Template('{{ max(foo, bar) }}').render(foo=2, bar=10, max=max)

'10'

In µWeb templates, there is no way to execute a passed in function. Registered functions will take the current tag value and transform it, but cannot accept two arguments, or even take a template variable as an argument to set up a function (like the subtract example above). The only way to get to the larger number is to write out the full conditional statement:

>>> from uweb.templateparser import Template

>>> template_str = '{{ if [foo] > [bar] }}[foo]{{ else }}[bar]{{ endif}}'

>>> Template(template_str).Parse(foo=2, bar=10)

'10'

Shortcomings like these mean that templates end up being very verbose and difficult to read. Other, more useful functions can be downright impossible to execute in the template, requiring the presenter code to stitch together multiple partial templates, making the final result more difficult to interpret than is needed.

No way to suppress template processing

There is no way to prevent interpretation of template syntax. This means that printing a word between brackets will be impossible if that word happens to be the name of a template variable. It also means that template syntax examples cannot be embedded into a template.

The official documentation works around this limitation by having the presenter place the contents of a static template example file into the general documentation template. Simplified for brevity, the presenter code and template look like this:

doc_fp = open(os.path.join(self.DOCUMENTATION_DIR, subject + '.html'))

return self.parser.Parse(

'documentation.html',

subject={'title': title, 'content': doc_fp.read()},

**self.CommonBlocks('Documentation'))

[header]

<div class="content">

<h2>µWeb documentation - [subject:title]</h2>

[subject:content|raw]

</div>

[footer]

While code examples and body text that looks like a tag might not be very common, the fact that they cannot be expressed without roundabout solutions is quite annoying. This will become especially problematic when undefined template variables are handled in a stricter manner.

No support for comments

Similarly, there is no way to indicate either line of block-style comments. This means that it’s not possible to quickly and non-destructively disable pieces of template. Without support for comments, disabling parts of a template can be done by temporarily deleting the relevant lines or wrap them in an always-False conditional block. However, since the block inside the conditional is still parsed, there is no allowance for bad syntax inside these faux-comments.

To be continued

The review of µWeb continues and is concluded in part two.

Appendix A: Lines of code in µWeb

The following counts are taken from the raw metrics section of Pylint. The code for the core of µWeb and the included libraries are listed separately. The additional modules are not part of µWeb but are required to run it. These are a mix of modifications on existing libraries and libraries built at Underdark.

µWeb core (1964):

- __init__.py: 119

- templateparser.py: 395

- model.py: 501

- request.py: 142

- response.py: 24

- standalone.py: 75

- pagemaker (708):

bundled code (2763)

- app: 144

- daemon: 390

- logging: 1271

- sqltalk: 958

Appendix B: Popularity of mod_python

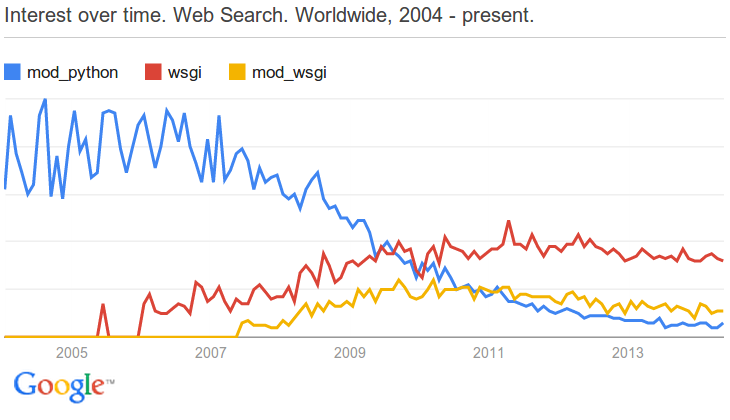

The following is a Google Trends graph that plots the relative popularity of mod_python, mod_wsgi and WSGI in terms of search volume:

The popularity of mod_python slowly declines and is overtaken by mod_wsgi and WSGI

Explore the full report in Google Trends.

Appendix C: Template syntax comparison

The following blocks compare the template syntax of Jinja2, Mako and µWeb’s template language. Demonstrated are:

- for-loop statement;

- attribute access;

- item (subscript) access.

<!-- jinja2.Template -->

<ul>

{% for member in group.members%}

<li>{{ member['name'] }}</li>

{% endfor %}

</ul>

<!-- mako.template.Template -->

<ul>

% for member in group.members:

<li>${member['name']}</li>

% endfor

</ul>

<!-- uweb.templateparser.Template -->

<ul>

{{ for member in [group:members] }}

<li>[member:name]</li>

{{ endfor }}

</ul>

Footnotes & References

| [1] | This ‘default to tag definition’ behavor is described at http://uweb-framework.nl/docs/TemplateParser#Simple-tags |

| [2] | Context variables in Mako: http://docs.makotemplates.org/en/latest/runtime.html#context-variables |

| [3] | Jinja2 has several distinct Undefined types that can be used: http://jinja.pocoo.org/docs/api/#undefined-types |

| [4] | Access to items and attributes on Jinja2 variables: http://jinja.pocoo.org/docs/templates/#variables |

Comments

comments powered by Disqus