Recently I was asked to sketch out a function that combines two sorted lists into a single (sorted) list. It’s a fun question with a couple of different answers, potentially all of them correct but with different pros and cons. There are two basic and one-line solutions that come from the Python standard library, so we’ll tackle those first.

Just sort it

Python’s sorting algorithm, Timsort [1], is pretty amazing. It’s stable (part of its mergesort heritage) and is designed to deal particularly well with partially sorted data. Which is exactly what we’ve been given: two runs that need to be merged. In fact, what we’ve been tasked with is the merge step of mergesort. So solution #1 is as simple as:

def combine_sorted(left, right):

return sorted(left + right)

This is easy to understand and obviously correct (we can’t really mess up sorting), as well as very succinct. However, it has a significant memory requirement as it copies both lists into a new one. Also, isn’t sorting going to get really slow with large lists? (spoiler: no it won’t, it’ll scale almost linearly.)

Merge them like heaps

Heaps are great! Also, sorted lists are heaps and Python has a wonderful module for dealing with heaps. In particular here we’re interested in the heapq.merge function. This takes any number of iterables and returns an iterator over the sorted output:

from heapq import merge

def combine_sorted(left, right):

return merge(left, right)

This solution is again easy to comprehend, and with some knowledge of the documentation and knowing we are using the function within its contract, it’s obviously correct. As a bonus we can combine infinitely long iterators without expending any additional memory beyond a small constant. If you have a number of generators that yield increasing (or decreasing, there is a reversed option) values with no known bounds, you can use heapq.merge to create a combined generator.

The downside? It’s approximately 3x slower than the simple combine-and-sort solution above. Having showed that we’re at least familiar with the available tools and provided solutions, let’s actually get into some programming. that.

Solving it the C-way

This is not the chapter where we break out our C-compiler and switch languages to solve the problem. We’re taking what I would consider the traditional approach to the problem:

- Start two index variables at 0;

- Compare the two objects at those indices in the list;

- Return the smaller one and increment its corresponding index;

- Loop until one list has reached its end;

- Return the remainder.

We are still using Python though, so we’ll create a generator rather than a list inside our function. One thing this saves us from is a large amount of method lookups and calls to append inside the main loop. A simple solution may look like this:

def combine_sorted(left, right):

len_left = len(left)

len_right = len(right)

i, j = 0, 0

while i < len_left and j < len_right:

if left[i] < right[j]:

yield left[i]

i += 1

else:

yield right[j]

j += 1

yield from left[i:]

yield from right[j:]

This is a pretty straightforward solution, and works pretty well. It won’t work for infinite lists (because of the len() call), but that’s not a requirement, just a nice to have. The merge operation performs three comparisons per iteration. Crucially, we know that only one index is going to be changed each iteration, yet we bounds-check both.

The loop conditional includes the case for zero-length lists, so if we alter that, we have to separately check for that case. That code will only need to run once though:

if not left:

yield from right

return

if not right:

yield from left

return

We’re mixing yield and return keywords here, which was forbidden in Python 2 but nowadays is a nice way of saying “my generator has finished”. It’s a little bit more verbose than ideal (return from left would be nice), but it’ll do.

Onto the loop itself. In addition to unnecessary comparisons, it retrieves the values from the two lists all the time, even when we know they haven’t changed, because the index hasn’t. This means we’ll have to hoist the very first values out of the loop. No big deal, especially now we already check both lists are non-empty.

Let’s briefly reconsider the termination condition for the loop. Why do we check bounds? Because accesses past the end of the list read random data and are undefined behavior?. No, this is Python, we get an exception. An exception that we can catch. Try/except blocks are really cheap as long as they don’t raise, and we know this raises only once (when we’re done with one list). So in keeping with the saying “[it’s] easier to ask forgiveness than permission” we should restructure the loop:

while True:

if left_val < right_val:

yield left_val

try:

i += 1

left_val = left[i]

except IndexError:

yield from right[j:]

return

else:

...

The loop body got a lot longer, but we have removed a lot of operations:

- Only one comparison per loop (compared to three before);

- Only one list access per loop (compared to three before);

- One try/except block per loop, but only a single exception needs to be caught.

These changes reduce the runtime of the function by ~30%. In other words, they get us from being barely faster than heapq.merge to approximately half as fast as naive sorting (which does have the advantage of being implemented in C). The full function for your pleasure:

def combine_sorted(left, right):

if not left or not right:

yield from left

yield from right

return

i, left_val = 0, left[0]

j, right_val = 0, right[0]

while True:

if left_val < right_val:

yield left_val

try:

i += 1

left_val = left[i]

except IndexError:

yield from right[j:]

return

else:

yield right_val

try:

j += 1

right_val = right[j]

except IndexError:

yield from left[i:]

return

So this works pretty well, but it’s not a particularly elegant or Pythonic solution. In the words of Raymond Hettinger: “There must be a better way.”

A better way with iterators

One of the things core to Python is the concept of iterators. Knowing that we only have to go over each of the inputs once, in the given order even, frees us from having to have random access. Turning them into iterators and simply getting one value at a time means that inputs don’t have to have a known size and can be of infinite size.

We’ll get into the loop in a moment, but before that, like with the improved C-way above, we’ll need to take care of the edge conditions to keep the loop as small and fast as possible. This means creating iterators and getting initial values. If getting initial values fails, we can abort early and return the other iterator (and the first value from the left if we retrieved it):

def combine_sorted(left, right):

left = iter(left)

right = iter(right)

try:

left_val = next(left)

right_val = next(right)

except StopIteration:

if 'left_val' in locals():

yield left_val

yield from left

yield from right

return

Combining the two initial value retrievals/checks is a little messier than before. By the time we know the right iterator is empty, we’ve already picked a value off the left and need to return that as well. In this case we check whether it exists in the local scope by means of a key check in locals(). If you really dislike this, the alternative is a slightly more verbose solution with two separate try/except blocks, where the second block needs to also yield the left_val. This result in near-duplication of code which may at first glance look like a bug.

The main loop for this solution will be super clean and tidy, because we can move the error/exhaustion handling outside of it. In fact, it only executes three statements per iteration:

- Compare the two current first-values

- Yield the smaller of the two

- Retrieve the next value from the corresponding iterator

try:

while True:

if left_val < right_val:

yield left_val

left_val = next(left)

else:

yield right_val

right_val = next(right)

except StopIteration:

yield max(left_val, right_val)

yield from left

yield from right

While the cost of starting a try block is very small, it is still measurable. The previous solution incurred that tiny startup cost for each iteration. This solution avoids that cost except for a single instance, by dealing with exhaustion outside of the while loop.

When one iterator is empty, the function just yielded the smaller of the two values. The final steps are then to yield the other, larger value, followed by the remaining values from both iterators (one of which is empty, so the order of the last two statements is arbitrary).

For a purely Python solution I think this is about as lean as the merge function is going to get. It’s a lot faster than the previous solution and it behaves more like a Python function should, dealing well with generators as inputs. It shaves off about 25% of the runtime from the previous solution, but it’s still over 50% slower than sorted(left + right) which is a bit disappointing. However, it has those other attributes that we appreciate:

- Small (constant) memory overhead

- The ability to merge iterators lacking explicit length

We can make one more code improvement for conciseness, albeit at a minute per-function runtime cost (measured as <1μs). Both the empty-iterator and the exhaustion handling code rely on except StopIteration. We can combine those two blocks and make a clear distinction between hot and cold code:

def combine_sorted(left, right):

left = iter(left)

right = iter(right)

try:

left_val = next(left)

right_val = next(right)

while True:

if left_val < right_val:

yield left_val

left_val = next(left)

else:

yield right_val

right_val = next(right)

except StopIteration:

if 'left_val' in locals():

if 'right_val' in locals():

yield max(left_val, right_val)

else:

yield left_val

yield from left

yield from right

Benchmark results

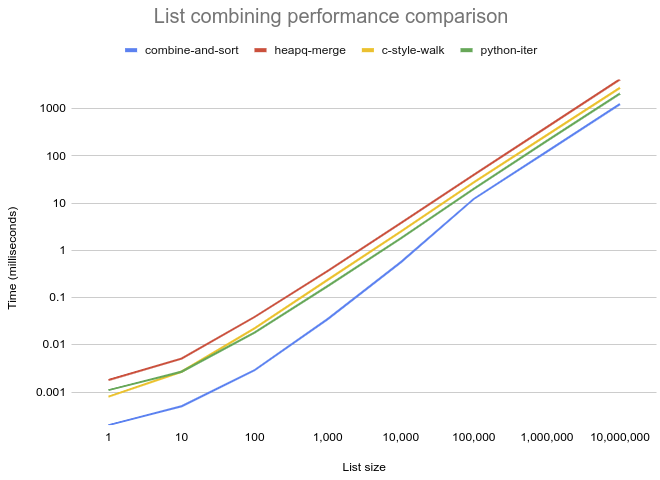

We’ve discussed relative performance of these solutions, but for some perspective, here are some absolute figures, taken from a benchmark Gist of these solutions. These are from Python 3.8 on an Intel i5-6200U:

Solution /size 1 10 100 1000 10K 100K 1M 10M ================== ======= ======= ======== ========= ======= ======== ========= ========== combine-and-sort 0.2us 0.5us 2.9us 35.1us 0.6ms 12.3ms 123.8ms 1251.3ms heapq-merge 1.8us 5.1us 38.9us 366.5us 3.8ms 39.8ms 407.3ms 4175.6ms c-style-walk 0.8us 2.7us 22.3us 236.9us 2.5ms 27.6ms 276.4ms 2777.2ms python-iter 1.1us 2.7us 18.2us 174.6us 1.8ms 20.1ms 207.9ms 2092.1ms

A graph plotted of the table of performance comparison above. This illustrates the massive performance gap between the combine-and-sort solution and all others and how it shrinks a lot past 10,000 items. It also shows the iter-based solution relies on sizes well over 100 to gain its second place and then remains steadily ahead of the C-style walk.

Conclusions

We’ve covered four different solutions to the problem of merging two sorted lists. They all have their pros and cons, though I would probably only use three of these, for broadly the following reasons:

- combine-and-sort: When the lists are bounded and overhead from copying is acceptable;

- python-iter: When inputs are potentially unbounded or memory is tight;

- heapq.merge: Like the above, but when there are more than two inputs to consider.

Footnotes

| [1] | Timsort is named after its inventor, Tim Peters, and has been the standard sorting algorithm for Python since 2.3. Tim Peters has been a long-time core developer of the Python language and you may also know his name for something called The Zen of Python. |

Comments

comments powered by Disqus