Fully randomized colors

In the previous two posts we’ve explored how to draw and tile hexagons, creating images that can be seamlessly repeated. We also briefly covered coloring them using a random color generator. The coloring process itself worked fine, but many times the created tiling turned out not very visually appealing, the colors of too harsh a contrast in tone and brightness.

In this post we’ll cover the creation of a mostly-random color generator. One that creates random colors within a certain fraction of the available colorspace.

Picking a color representation

There are a few different ways to describe colors in RGB colorspace, providing us with different approaches on how to restrict the available portion to select colors randomly from:

- RGB: Red, Green and Blue values — A direct representation of the intensity of each of the color components.

- HSV: Hue, Saturation, Value (brightness) — A cylindrical color mapping, common in color wheels in various graphics programs

- HSL: Hue, Saturation and Lightness — Another cylindrical color mapping, similar to HSV but with a few different behaviors which we’ll discuss in a moment

Any of the above could be used, and all three have potentially interesting behavior when certain values are kept constant, or only allowed to vary by a small amount. If we would like a behavior where we can restrict the hue of the color but have full variation in lightness and color intensity, the direct RGB mode is ruled out.

The choice between HSV and HSL mostly comes down to a matter of taste. Intuitively, when I read a color where all three channels are maxed, I would expect that to be a fully saturated and maximally intense color. HSV gives us that result, where HSL gives us full white (the maximum chroma is achieved at L=0.5). For this reason, let’s take HSV as our color coordinate system.

HSV to RGB in Python

Conveniently, Python comes with a library that does transitions between different color coordinate mappings of RGB. The colorsys library contains a pair of functions to convert between RGB and HSV (as well as HSL and YIQ). There is a small catch though: all inputs and outputs are floating point numbers between 0 and 1, rather than the 0-255 integers we typically see for RGB.

This is simply because there is nothing restricting RGB to exactly eight bits per channel. In the 90’s, 16-bit color modes were common, where red, green and blue were represented by 5, 6, and 5 bits respectively. And on the other end of the spectrum, digital camera RAW output typically contains 12 or 14 bits per channel worth of color information [1]. This is also known as the dynamic range of the colors.

The typical dynamic range for computer monitors, and consequently for most image formats, is the aforementioned eight bits. PIL (and with it, aggdraw) accepts color channel values in an 8-bit range, so we need need to map the 0-1 floating point output to a 0-255 integer range and vice-versa.

import colorsys

def to_float(value, domain=255):

return float(value) / domain

def from_float(value, domain=255):

return int(round(value * domain))

rgb = 10, 150, 255

hsv = colorsys.rgb_to_hsv(*map(to_float, rgb))

print hsv # (0.5714285714285715, 0.9607843137254902, 1.0)

rgb = map(from_float, colorsys.hsv_to_rgb(*hsv))

print rgb # [10, 150, 255]

Building the randomizer

Let’s build a simple randomizing function where can lock down the hue. To make the function slightly friendlier to our human inputs, we’ll accept hue inputs as degrees, mimicking the color circle as commonly seen in image editing software.

import colorsys

import random

def random_color(hue=None, sat=None, val=None):

hue = hue / 360.0 if hue is not None else random.random()

sat = sat if sat is not None else random.random()

val = val if val is not None else random.random()

to_eightbit = lambda value: int(round(value * 255))

return map(to_eightbit, colorsys.hsv_to_rgb(hue, sat, val))

random_color(hue=0) # something red: [186, 98, 98]

random_color(sat=0) # something gray: [134, 134, 134]

random_color(sat=1, val=1) # max chroma: [36, 0, 255]

random_color(hue=0)

Random numbers in a restricted range

We can now generate random colors where not all input wheels are freely spun, but one or more are held down. This way we can match tone or intensity, but depending on the exact input that’s locked, it can be a bit boring, or still way too colorful. Exactly one tint of red with only variations in saturation and lightness is boring; getting colors of all hues is too much. What we need is a way to clamp the possible outcomes within a certain range.

The following snippet defines a function that returns functions which can be used to generate our channel values. Providing it with a single number returns a function that always returns that number (the constant option from our previous example). Providing it with a 2-tuple of numbers returns numbers within that range, and providing None returns a ‘regular’ random number generator in the range 0-1:

def channel_picker(value):

if value is None:

return random.random

if isinstance(value, tuple):

start, stop = value

return lambda: random.random() * (stop - start) + start

return lambda: value

>>> rand = channel_picker((0.4, 0.6)) # Randoms in given range

>>> [rand() for _ in range(3)]

[0.4785833631009269, 0.4449304246805125, 0.5504729222480945]

>>> rand = channel_picker(0.76) # Constant values

>>> [rand() for _ in range(3)]

[0.76, 0.76, 0.76]

Piecing it all together

The channel_picker() as it’s implemented above needs to be adapted to work with our hue values which are in the 0-360 range. It also needs to be connected to the code that constructs the number and then scales it out to fit the 8-bit integer range. With all of these things being very purpose-built, a simple class should do the trick:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 | import colorsys

import random

class HsvColorGenerator(object):

def __init__(self, hue=None, saturation=None, value=None):

self.h_func = self._channel_picker(hue, scale=360)

self.s_func = self._channel_picker(saturation)

self.v_func = self._channel_picker(value)

def __call__(self):

"""Returns a random color based on configured functions."""

hsv = self.h_func(), self.s_func(), self.v_func()

expander = lambda value: int(round(value * 255))

return tuple(map(expander, colorsys.hsv_to_rgb(*hsv)))

def _channel_picker(self, value, scale=1):

"""Returns a function to create (restricted) random values."""

if value is None:

return random.random

scaler = self._scale_input(scale)

if isinstance(value, tuple):

start, stop = map(scaler, value)

return lambda: random.random() * (stop - start) + start

else:

value = scaler(value)

return lambda: value

def _scale_input(self, scale_max):

"""Creates a function that compresses an range to [0-1]."""

scale_max = float(scale_max)

return lambda num: num / scale_max

|

Upon initialization, the class sets up the three functions to return the hue, saturation and value components of the color. These can be completely random, within a given range, or fixed. The code using them isn’t aware and doesn’t care, as long as the numbers are in the right range. [2]

When the generator is used by calling the instance, a (possibly not quite) random value is taken from each of the hue, saturation and value generators. This is then converted to RGB, scaled to fit an 8-bit integer range, and returned.

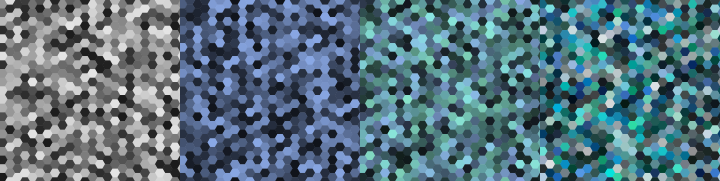

Examples in blue

In the last code example, we update the tiling creator from the last post to use an externally supplied random color generator, and supply it with instances of the HsvColorGenerator. We run the creator function several times, each time with a different random color generator. We start off with a grayscale variant and increase color and tint ranges with every iteration.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 | def draw_tiling(repetitions, edge_length, color_func):

hexagon = HexagonGenerator(edge_length)

canvas = create_canvas(hexagon.pattern_size, repetitions)

draw = Draw(canvas)

for row in range(hexagon.rows(canvas.size[1])):

colors = [color_func() for _ in range(repetitions)]

for column in range(repetitions + 1):

color = colors[column % repetitions]

draw.polygon(list(hexagon(row, column)), Brush(color))

for column, color in enumerate(colors):

draw.polygon(list(hexagon(-1, column)), Brush(color))

draw.flush()

canvas.show()

def random_blues():

# Plain grayscale to start off with

yield HsvColorGenerator(saturation=0, value=(.1, .9))

# Monochrome blue with brightness variation

yield HsvColorGenerator(hue=220, saturation=.4, value=(.1, .9))

# Wider chroma with a fixed saturation

yield HsvColorGenerator(hue=(180, 220), value=(.1, .9), saturation=.4)

# Removed fixed saturation for a more lively image

yield HsvColorGenerator(hue=(180, 220), value=(.1, .9))

def main():

for color_func in random_blues():

draw_tiling(12, 5, func)

|

Some results of the above script.

And that is it for this short series on creating hexagon tilings and coloring them. An idea that got sparked by some random website, explored on a delayed and detoured train ride home, and put into words over the span of a fortnight. And it resulted in a less boring blog theme to boot! If you’ve made something similar, more awesome, derived from this, or a suggestion on where to take this, let me know with a comment.

Footnotes

| [1] | The actual bit-depth depends on the make and model of the camera. Most cameras will in addition share some tonal information across pixels (one blue, one red and two green pixel sensors for four RGB output pixels), but even so, the range is significantly larger than eight bits. For more: raw image format |

| [2] | Actually, the ranges do not strictly have to be in the 0-1 domain. The converter functions in colorsys seem happy enough to receive any number, and will do something with it. For hue it goes around the color wheel, causing hue=(300, 400) to result in purples and reds to be generated. The behavior of saturation and value are significantly more erratic, but may be interesting to play with nonetheless. |

Comments

comments powered by Disqus